(actually covers June 18-21 and August 23; reposted from here)

We went to Yellowstone. We did.

But I won’t bore you with the details of that, because they’re details you could find in any tourist guide or travel book, and that’s not what’s important here.

The point is we went searching for the Native American dream, and to understand the way this twisted world and our machinations and industry on the body of the earth have changed and corrupted and re-inspired it, and where it lies today, and a path toward hope. We came looking for a glimpse of a dream, or perhaps a nightmare, and somewhere along the way, dizzy, dirty, and overwhelmed, we lost track of it.

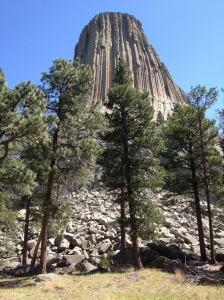

While we were doing things like looking for fossils of ancient, esoteric sea creatures in the rugged, rocky hills on the road to Cody (and ending up chasing horny toads instead) where the sleek, brown teeth of prehistoric squid lay sprawled across the pebbles like so many seashells, or while we were standing dangerously on the edges of cliffs at Devil’s Kitchen (or Devil’s Lunchbox as Patrick often called it) where the painted canyon below us spilled out in an overflow of pastel colors and wild, jagged formations that looked like a madman’s map of Mordor, or while we were looking at waterfalls and massive, man-made dams at the edge of Yellowstone and climbing hills we weren’t supposed to, to look down at the great crowd of students we were supposed to be watching, or while we were shivering and wrapped in sleeping bags on the icy, windy shores of this great, ocean-sized lake that appears out of nowhere in the center of the caldera that is Yellowstone and greets you like the arctic sea, while we were walking amidst the hot springs and geysers that funnel boiling water from under the earth and reek of sulfur and cover the blue sky in thick, gray steam, while we were waiting for the bison we’ve been looking for for so long to cross the roads while tourists took tens of hundreds of pictures, while we were hiking along the circumference of the Grand Canyon of Yellowstone and gazing in awe at its walls of yellow stone for which Yellowstone wasn’t named, while we were chasing bears and hitting antelopes and herding high schoolers…

The truth is I left Yellowstone more than a month ago. We drove down to Salt Lake City in the long, restless PM, and took a plane out the next morning, and finally returned home to Indianapolis, red-eyed and sleepless, after an eight hour layover in Denver. The journey was finished, but the story wasn’t over yet. Something was missing.

The truth is I left Yellowstone more than a month ago. We drove down to Salt Lake City in the long, restless PM, and took a plane out the next morning, and finally returned home to Indianapolis, red-eyed and sleepless, after an eight hour layover in Denver. The journey was finished, but the story wasn’t over yet. Something was missing.

So here I am, sitting in my cool, air-conditioned apartment in West Lafayette, on the third day of classes re-starting, sipping green tea and listening to music from the stereo speakers attached to my HDTV, staring at an article about how 2,000 acres of land in the Black Hills called Pe’ Sla, an area sacred to the Sioux, the Cheyenne, the Arikara, and Arapahoe, is about to be auctioned off by a private owner to the highest bidder. The tribes have raised money in hopes of buying back the land once taken from them and still sacred to them, but the “property” is expected to sell for approximately eight times the value they’ve raised. The state of South Dakota will likely put a road directly through the sacred areas, and open the land for private development.

This is not the Native American dream.

On our last nights out there, in our cabins in West Yellowstone, we sat and talked in hushed tones about all the things we’d seen. The sadness. The greed. The hopelessness. The false hope. The despair. The futility. The beauty. The reaping and weeping.

On our last nights out there, in our cabins in West Yellowstone, we sat and talked in hushed tones about all the things we’d seen. The sadness. The greed. The hopelessness. The false hope. The despair. The futility. The beauty. The reaping and weeping.

We talked about Leon, the Lakota small business owner we met on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, who owns a small but popular coffee shop. He’d talked to us about his struggles on and off the reservation. His attempts to do things that weren’t designed to be done, here and elsewhere. His return to the reservation. His opening of the coffee shop. Today, he is successful. He’s writing a book. There is a glimmer of the dream.

I wonder if he knows about this auction. I wonder if he’s tried to do anything. I wonder if there’s anything he can do. (I know he can make a damn good cup of coffee.)

The stars on those nights out there were clear, but the future they foretold was not.

As I sat there, listening to my friends and compatriots on the journey, I began to wonder if  we weren’t misguided from the very beginning. We came this way in search of answers, but we’ve found only scars and scar tissue and more unanswered questions. We’ve learned so many things, but we still don’t understand what they mean. We don’t understand a thing. The things we’ve learned along the way are the smoke of a distant signal fire, but where does it lead? It’s dim, and there’s a storm in the distance and a flood at our backs, but though the rain will muddy and obscure the little trail we’re on, it’s what’s needed to invigorate the earth beneath our feet. The smoke and the distant fire we see is a sign that though the path we tread may be a lonely one, there have been others on it before us, and we are not alone. We are never alone. And we need to get there, to tend the fire at the other end of this rocky path, and keep it lit, and kindle it to burn brighter for those that follow us. The people we’ve talked to are waiting for us. The dreams of so many are waiting on us.

we weren’t misguided from the very beginning. We came this way in search of answers, but we’ve found only scars and scar tissue and more unanswered questions. We’ve learned so many things, but we still don’t understand what they mean. We don’t understand a thing. The things we’ve learned along the way are the smoke of a distant signal fire, but where does it lead? It’s dim, and there’s a storm in the distance and a flood at our backs, but though the rain will muddy and obscure the little trail we’re on, it’s what’s needed to invigorate the earth beneath our feet. The smoke and the distant fire we see is a sign that though the path we tread may be a lonely one, there have been others on it before us, and we are not alone. We are never alone. And we need to get there, to tend the fire at the other end of this rocky path, and keep it lit, and kindle it to burn brighter for those that follow us. The people we’ve talked to are waiting for us. The dreams of so many are waiting on us.

we weren’t misguided from the very beginning. We came this way in search of answers, but we’ve found only scars and scar tissue and more unanswered questions. We’ve learned so many things, but we still don’t understand what they mean. We don’t understand a thing. The things we’ve learned along the way are the smoke of a distant signal fire, but where does it lead? It’s dim, and there’s a storm in the distance and a flood at our backs, but though the rain will muddy and obscure the little trail we’re on, it’s what’s needed to invigorate the earth beneath our feet. The smoke and the distant fire we see is a sign that though the path we tread may be a lonely one, there have been others on it before us, and we are not alone. We are never alone. And we need to get there, to tend the fire at the other end of this rocky path, and keep it lit, and kindle it to burn brighter for those that follow us. The people we’ve talked to are waiting for us. The dreams of so many are waiting on us.

we weren’t misguided from the very beginning. We came this way in search of answers, but we’ve found only scars and scar tissue and more unanswered questions. We’ve learned so many things, but we still don’t understand what they mean. We don’t understand a thing. The things we’ve learned along the way are the smoke of a distant signal fire, but where does it lead? It’s dim, and there’s a storm in the distance and a flood at our backs, but though the rain will muddy and obscure the little trail we’re on, it’s what’s needed to invigorate the earth beneath our feet. The smoke and the distant fire we see is a sign that though the path we tread may be a lonely one, there have been others on it before us, and we are not alone. We are never alone. And we need to get there, to tend the fire at the other end of this rocky path, and keep it lit, and kindle it to burn brighter for those that follow us. The people we’ve talked to are waiting for us. The dreams of so many are waiting on us.

I think maybe we were wrong — maybe I was wrong — to think that we’d find a dream of any kind out there. What we found were memories. Or maybe prayers. But maybe we needed to go out there to find the dream within us. Maybe I needed to go.

To learn what needs to be done. To learn what should not be done. To learn from the successes and failures and mistakes. To learn from the tears shed and the stories behind them. To rediscover things forgotten, but never lost. That some things we can never buy back, but some things we can change. That you can sell your soul, but never your heart.

I hope one day to return to the Black Hills and walk in Pe’ Sla, as I walked up Bear Butte, on its stony paths lined with trees with branches tied by ribbons of prayer, where no wars were ever fought and no battles ever joined, where people went for peace, and where all tribes could go to talk to the wind and the earth. I hope I can bring my children to a place that isn’t a parking lot, where we don’t need water slides to feel the rush of energy, and the stars are clear and the future is bright.

I don’t know what will happen, but I can hope.

But we know it’s not enough to keep hoping.

So we will keep working. There is a dream to be tended. Our friends are waiting.

Update: Two days after the writing of this post, the auction of Pe' Sla was cancelled by the owners for reasons they declined to make public; the sacred land remains private property, publicly listed, and its ultimate fate remains uncertain.

Update: Two days after the writing of this post, the auction of Pe' Sla was cancelled by the owners for reasons they declined to make public; the sacred land remains private property, publicly listed, and its ultimate fate remains uncertain.