We’re up in the AM and moving out of Lakota land up toward Yellowstone again, but first we have a few more stops to make.

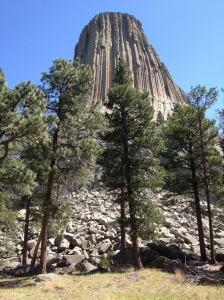

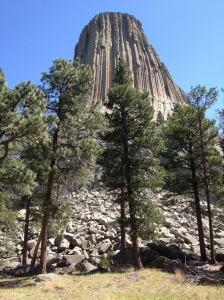

First we find ourselves mock-hitchhiking to that Great Gray Tooth jutting from the desert. It looks like a molar rising from the gums of the land in the distance from where we take out first pictures and stick our thumbs out like idiots. It wasn’t my idea. Someone thought it would make a good picture. No one stops, just like they wouldn’t have if and when we’d have been serious in this in those days long ago when we would have been without cell phones — that blessed, hellish, blissful existence I can’t imagine.

We get there and all of a sudden it’s massive and looming and we’re in its never-ending shadow. It’s a castle. A keep. A fortress. . . A tower! Devil’s Tower, they call it. Bear Den. This whole big intrusion of igneous rock that’s fought through sediment and erosion and still stands so tall and imposing. Terrifying crevices creep down its side. They’re scars on its bony flesh clawed out by a great, ancient, and horrifying bear as tall as clouds with a roar like thunderstorms. It has an awesome power that trembles you to your soul, like that intense prayer wind that permeated Bear Butte, but there are more people here, and it’s almost like they don’t quite realize it. What’s before them. What’s above them. They sense it, sense something. They see it, but they don’t see it, like so many of these places. We walk around it, and it eyes us the whole way, and we’re always in its shadow.

shadow. It’s a castle. A keep. A fortress. . . A tower! Devil’s Tower, they call it. Bear Den. This whole big intrusion of igneous rock that’s fought through sediment and erosion and still stands so tall and imposing. Terrifying crevices creep down its side. They’re scars on its bony flesh clawed out by a great, ancient, and horrifying bear as tall as clouds with a roar like thunderstorms. It has an awesome power that trembles you to your soul, like that intense prayer wind that permeated Bear Butte, but there are more people here, and it’s almost like they don’t quite realize it. What’s before them. What’s above them. They sense it, sense something. They see it, but they don’t see it, like so many of these places. We walk around it, and it eyes us the whole way, and we’re always in its shadow.

shadow. It’s a castle. A keep. A fortress. . . A tower! Devil’s Tower, they call it. Bear Den. This whole big intrusion of igneous rock that’s fought through sediment and erosion and still stands so tall and imposing. Terrifying crevices creep down its side. They’re scars on its bony flesh clawed out by a great, ancient, and horrifying bear as tall as clouds with a roar like thunderstorms. It has an awesome power that trembles you to your soul, like that intense prayer wind that permeated Bear Butte, but there are more people here, and it’s almost like they don’t quite realize it. What’s before them. What’s above them. They sense it, sense something. They see it, but they don’t see it, like so many of these places. We walk around it, and it eyes us the whole way, and we’re always in its shadow.

shadow. It’s a castle. A keep. A fortress. . . A tower! Devil’s Tower, they call it. Bear Den. This whole big intrusion of igneous rock that’s fought through sediment and erosion and still stands so tall and imposing. Terrifying crevices creep down its side. They’re scars on its bony flesh clawed out by a great, ancient, and horrifying bear as tall as clouds with a roar like thunderstorms. It has an awesome power that trembles you to your soul, like that intense prayer wind that permeated Bear Butte, but there are more people here, and it’s almost like they don’t quite realize it. What’s before them. What’s above them. They sense it, sense something. They see it, but they don’t see it, like so many of these places. We walk around it, and it eyes us the whole way, and we’re always in its shadow.

Then we set out for the throbbing center of the scar tissue of this land: the rolling hills called Little Bighorn, where it all went down, and dreams flickered like fire on ice.

There is a visitors’ center and little gravel paths with gravestones all marked along their ways and a sprawling cemetery that takes up so much of the land. We don’t go to the cemetery with all its whale-white markers. Instead, we walk up the hill.

I walk up the hill.

The hill is split down its heart by a black paved road.

On one side, there is a bleached monument of pale gray stone and names of US soldiers. It stands in the center of a small square of bright green grass roped off from the rest of the world. The whole thing is foreign and barbaric and looks nothing like these hills.

On the other side, there is a mound of earth. This earth. Brush and grass live on it. Through the mound are circular walls of rock inset with great metallic plaques of the indigenous peoples who fought and hoped and died here for the lives and the ways of the lives of their peoples. In a window in the earth are sculpted outlines in metal and wire of the warriors on their horses, and behind them the great plains and the green-brown hills go on and on. The air is heavy with them — with the breath of the Cheyenne and Arapaho and Crow and Sioux and Arikara who bled here. The Indian memorial gives me hope.

The Indian memorial gives me hope.

The Indian memorial gives me hope.

The Indian memorial gives me hope.

And my heart goes out to the white mothers of the uniformed sons who died here under the command of that black-souled man named Custard, but though their names are written here, I feel none of their presence in this place. Because this is not their home. And I can only hope they have found their way back, and are forever freed.

But of the Indians who fell here . . . they are more than just sculptures and metal outlines. More than just a memorial. They are here. They are here in every fiber of the earth and sky. If you look closely in the dust and the brush, you can see them riding. If you listen closely in the whisper of the wind, you can hear them singing. Put your ear to the ground and the heartbeat is earth and mother and horses’ hooves and drums and prayer. Their breath is strong and good in the air.

I watch the families file past the stones marking the places where soldiers fell. I can only wonder how they feel and what they think. Are they sad? Do they feel guilty? Proud? What is in their hearts in this violent, pacific, Pyrrhic place? Do they feel what their country lost here? Do they feel what we failed to win?

I remember what was said at a little coffee shop on the Pine Ridge reservation. They took our children. Kill the Indian and save the man, they said.

There are little children here. Do they know I’m Indian? Do they know what it means to kill an Indian? Do they know what this place means? What really happened?

And here am I. Am I an Indian? Am I a man?

I turn back and close my eyes and try to listen to the whispers in the wind of the people who were here long before I. I can only imagine that in that spirit world where they must reside, they are riding now, and the buffalo are back, and they number greater than ever.

No comments:

Post a Comment